Abyssinian Difficulty. The Emperor Theodorus and the Magdala Campaign 1867-68.

Édition

Éditeur : Oxford University Press

Lieu : Oxford New York Dehli Nairobi

Année : 1979

Langue : anglais

Description

État du document : bon

Références

Réf. Biblethiophile : 003693

Réf. UGS : 91020000

Première entrée : 1868

Sortie définitive : 1868

COLLATION :

XIV, 240 p.

En savoir plus

Vu par biblethiophile

À défaut d’une étude monographie plus récente, le travail de Darell Bates publié en 1979 reste l’unique synthèse à la disposition du lectorat et des chercheurs. Le premier sera comblé par les détails, les anecdotes relevés par l’auteur alors que le second se réjouira de découvrir de nouvelles sources, parmi lesquelles les archives familiales d’Albert Napier, le fils de Lord Robert Napier of Magdala. Cependant, le chercheur restera sur sa fin en ne découvrant qu’une bibliographie succincte et l’absence de citations de source. Qu’il s’abstienne de dénigrer le travail de Bates car bientôt un demi-siècle se sera écoulé sans qu’un historien n’ait pris le taureau par les cornes et n’ait dompté le sujet dans les règles de l’art.

Présentation par l’éditeur

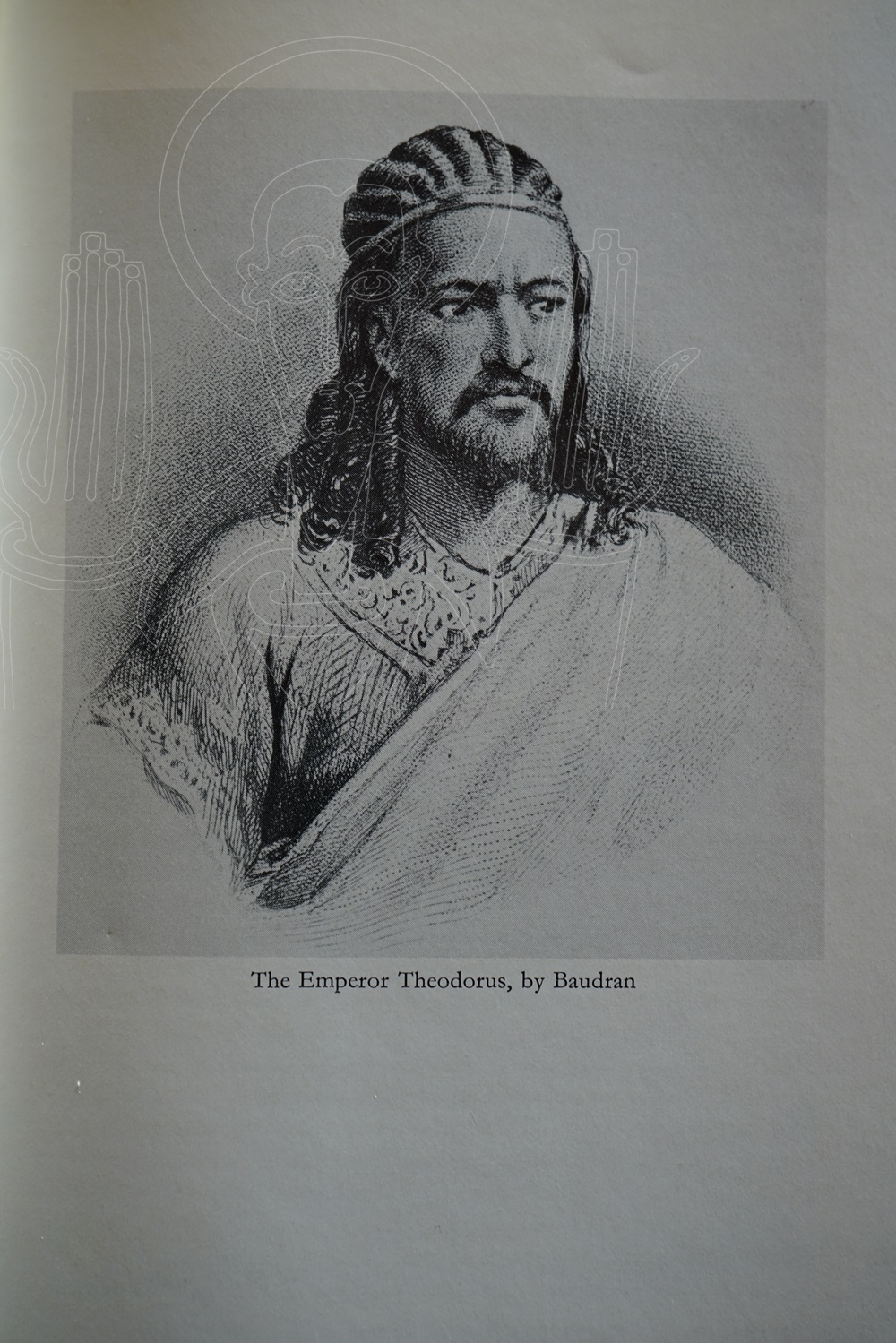

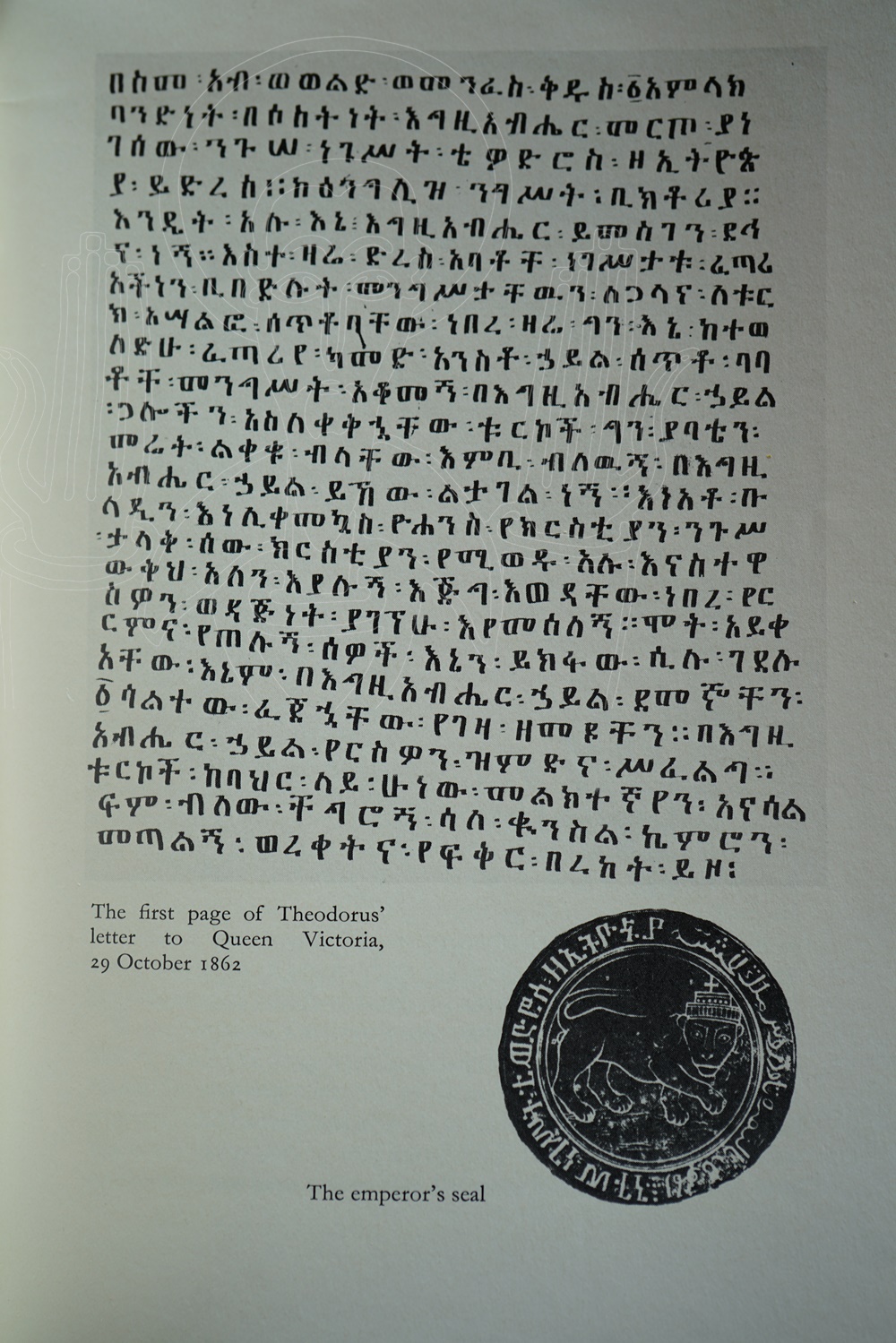

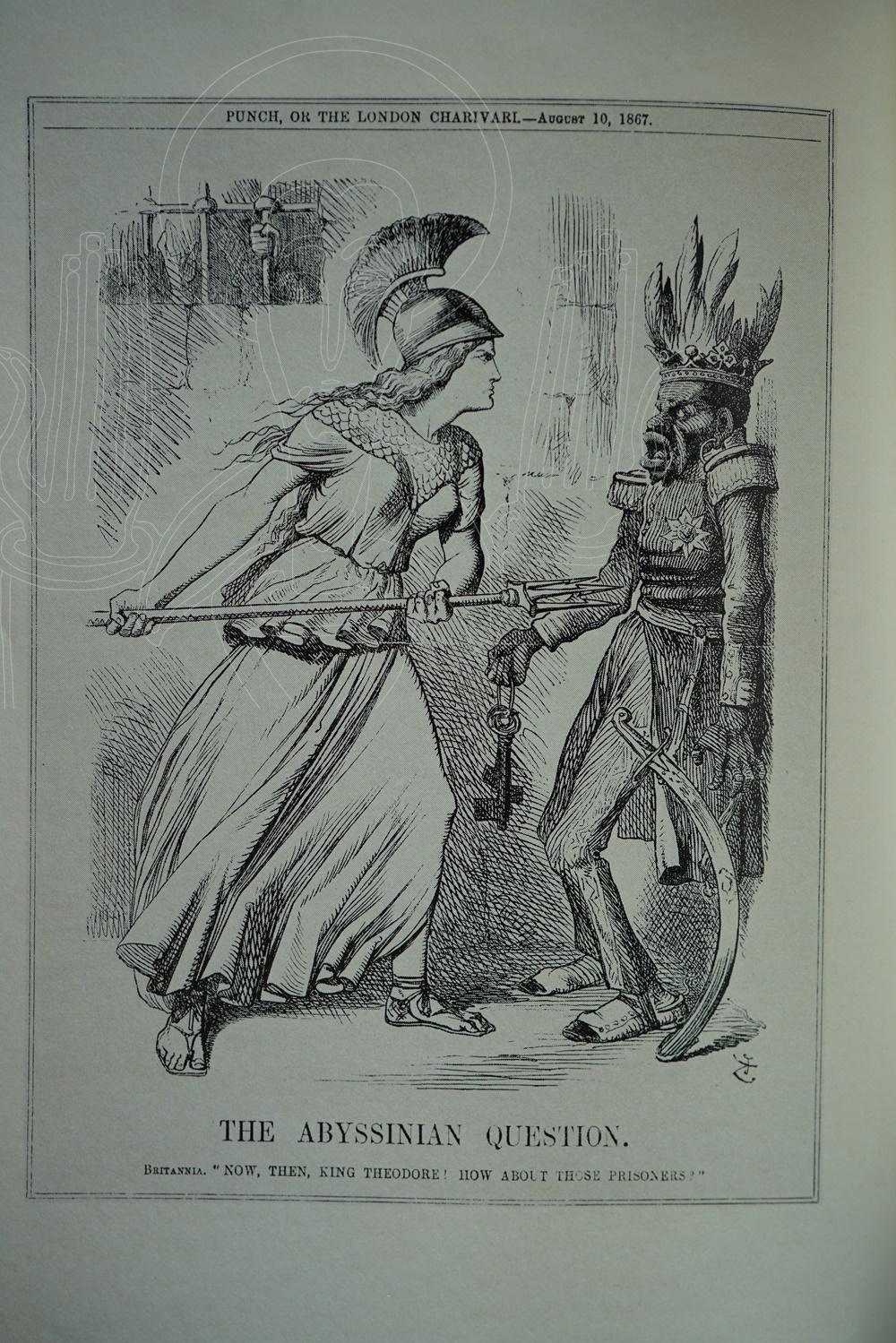

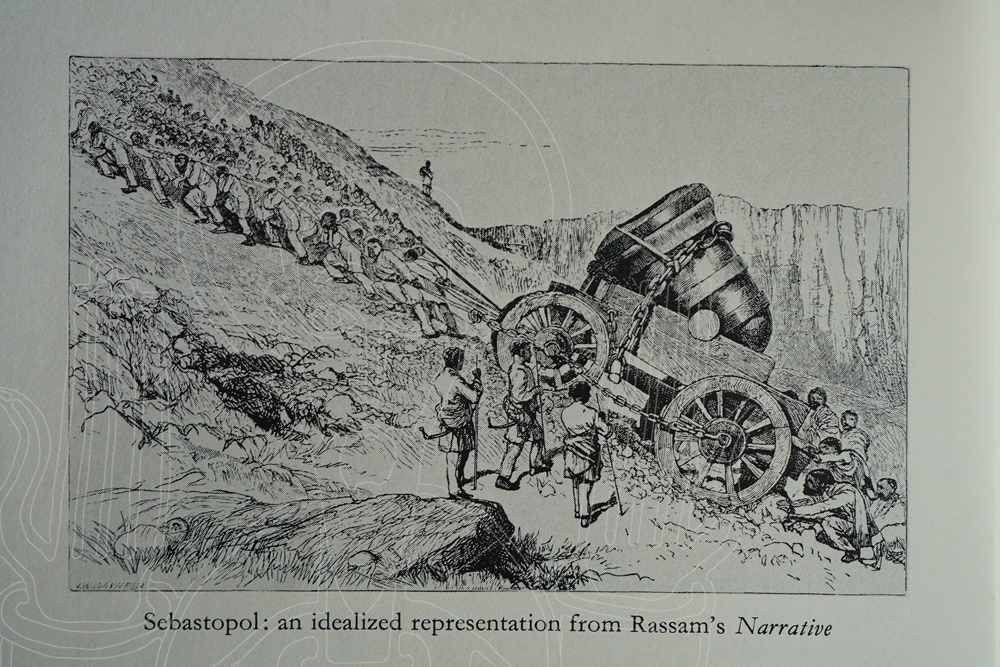

By energy, intelligence, and ruthlessness he mastered most of his rival chieftains and became ‘the Elect of God, the Slave of Christ, the King of Kings and Emperor of all Abyssinia’, claiming descent from King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. He admitted European traders, and missionaries (but only to convert the pagans and Black Jews), and encouraged the introduction of techniques, from printing to cannon-casting, that began the modernization of Ethiopia. He made particular friends with the British consul, and in October 1862 he sent a cordial letter, proposing diplomatic relations, as from the ruler of one empire to another, to Queen Victoria. His name was Theodorus (Tewodros to modern Ethiopian scholars, Theodore to 19th-century Europeans), and when, a year later, he had still not had a reply from the Queen of England, he imprisoned the new British consul and clapped him in irons, and in due course he added about sixty Europeans and their dependants to his tally, holding them as hostages.

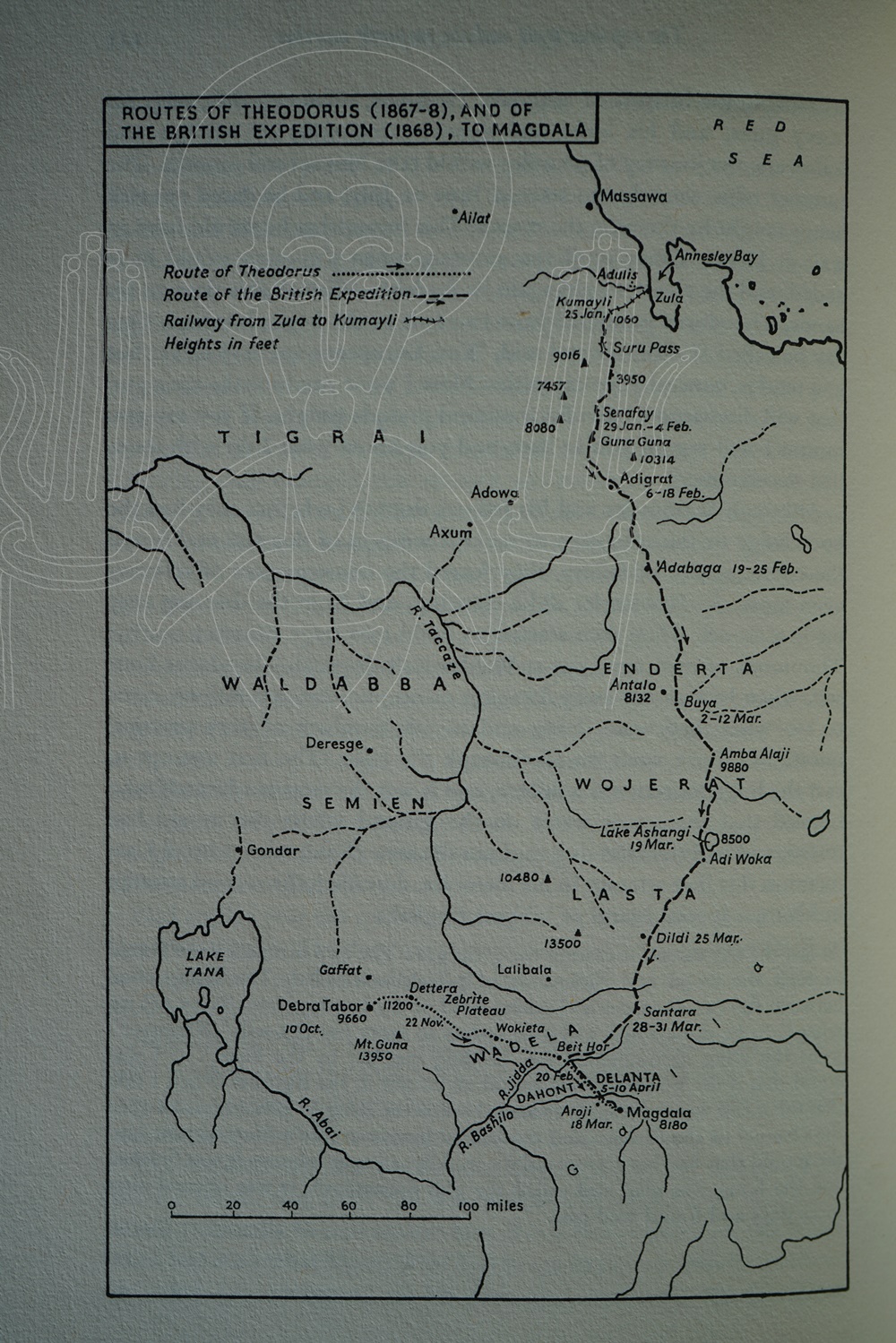

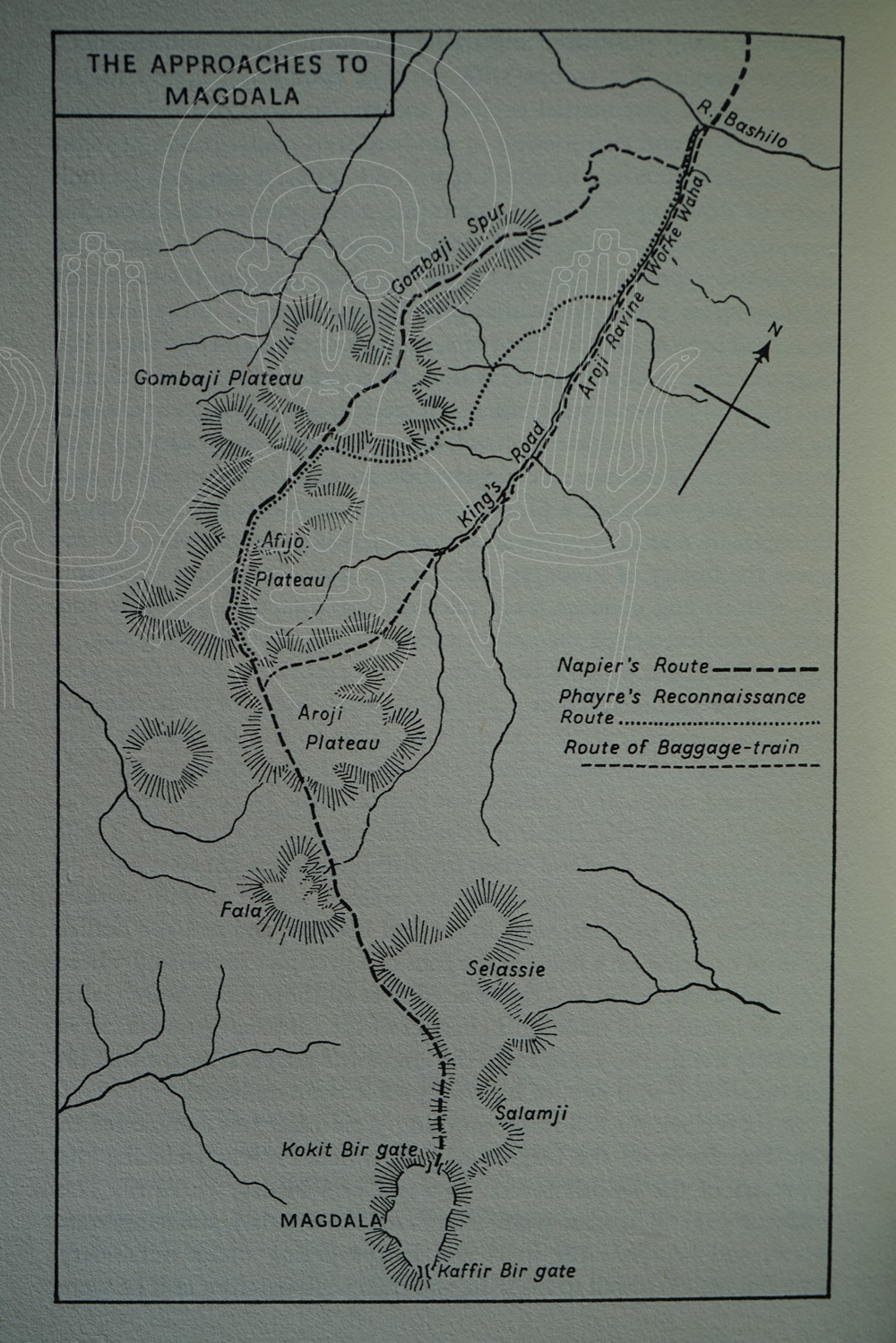

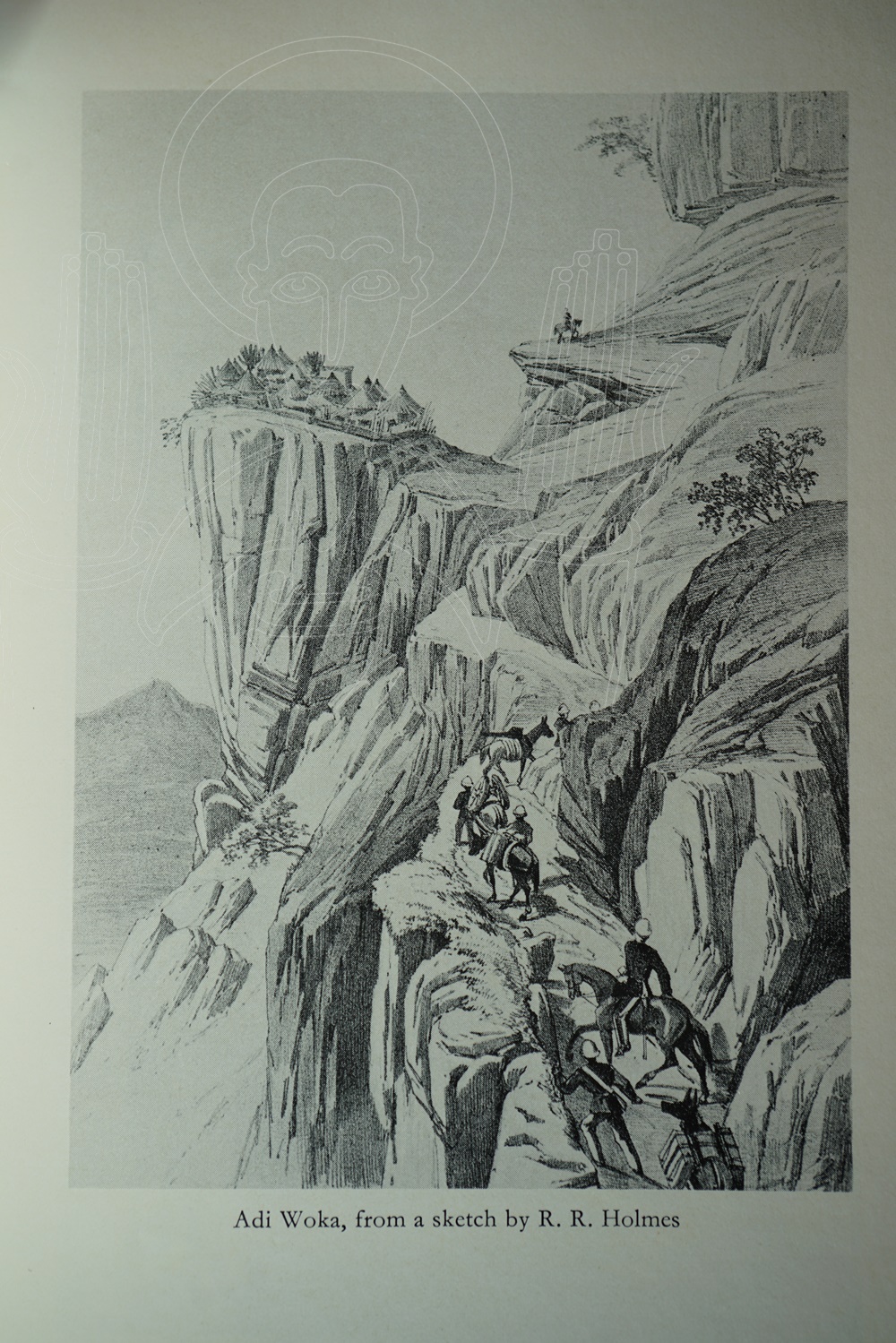

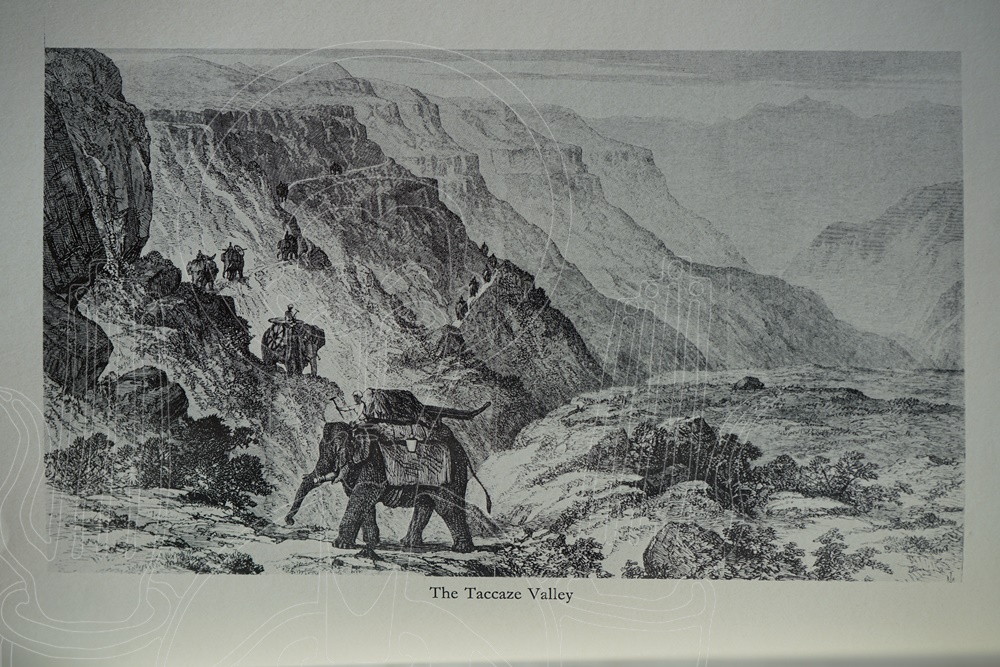

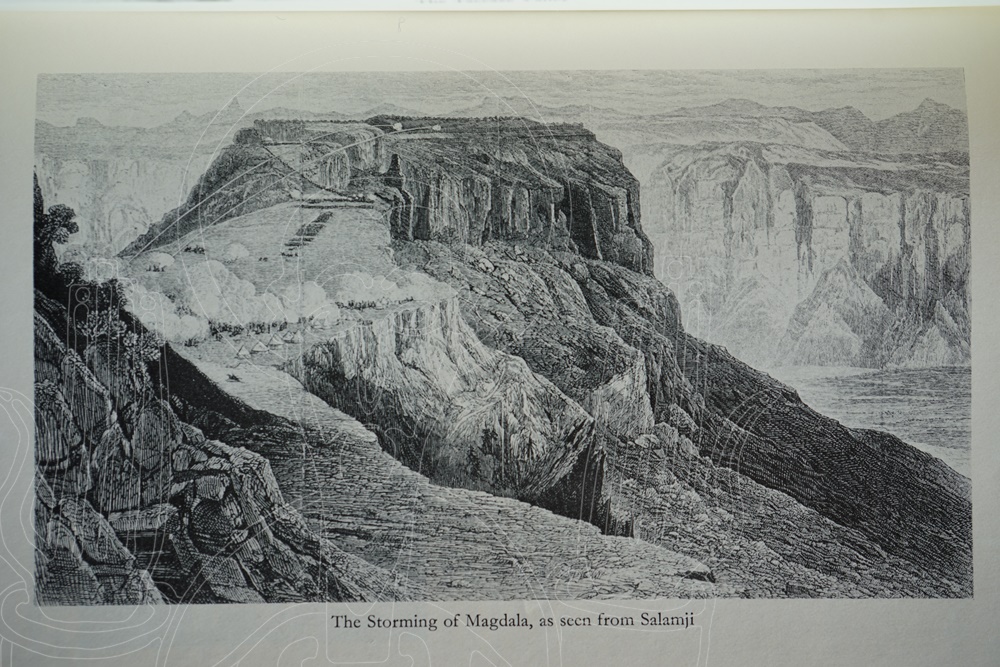

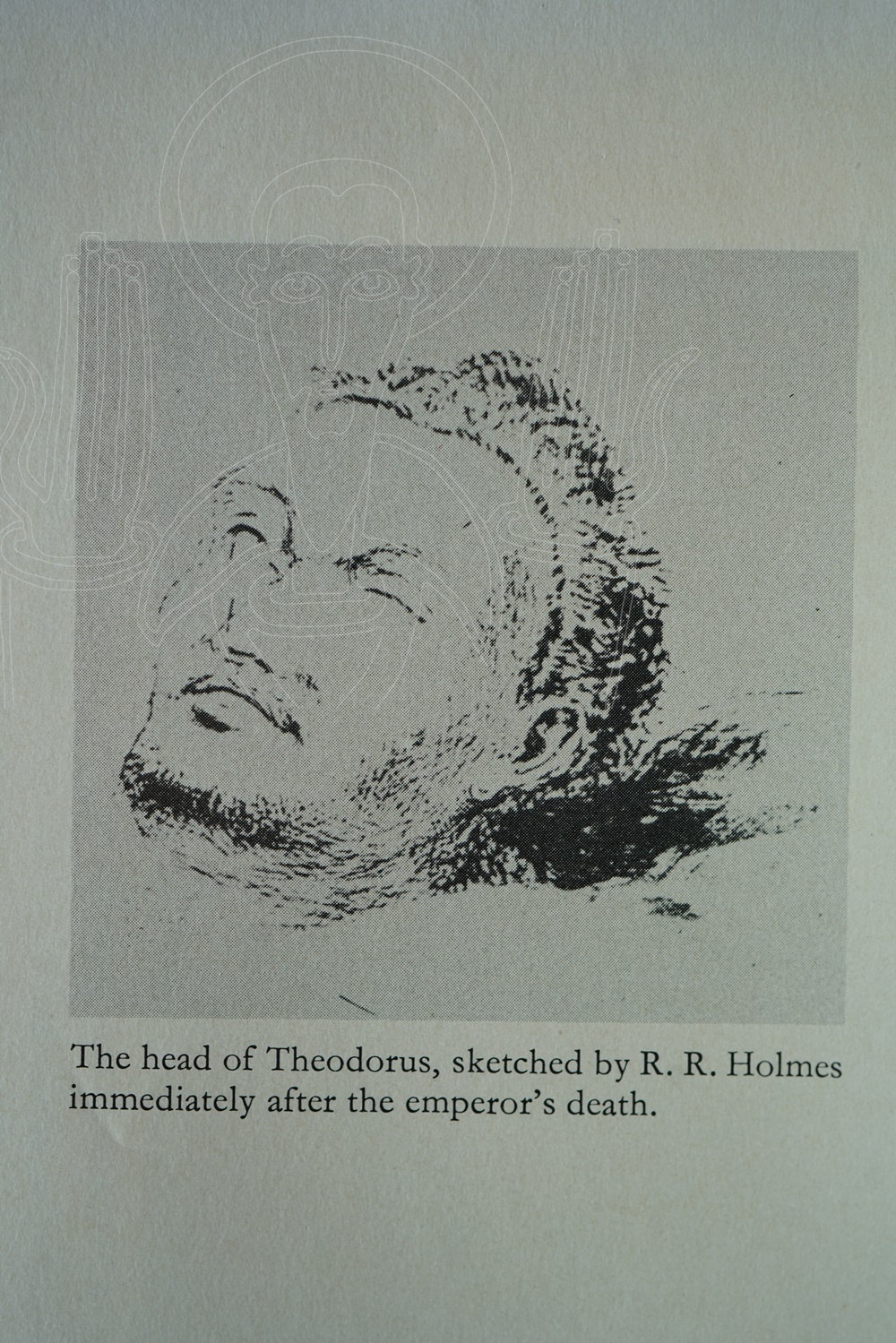

In recent years it has been a matter of only a few days before governments have decided how to rescue their nationals held hostage, and a matter of hours to snatch them away by air. But in the 1860s it took four years of devious and reluctant political and diplomatic manoeuvring, and then a full-scale expedition launched from India – with the latest in military technology such as breech-loading rifles, searchlights, a railway from the port of disembarkation, and official photographers – lasting several months, before the British army under General Napier after a 400-mile march through precipitous mountains defeated the Abyssinian forces in April 1868 in a battle outside the seemingly impregnable citadel of Magdala. Napier stormed the fortress, and released every one of the Europeans (whose number had gone up, as two of the missionaries’ wives had had babies in captivity). The Emperor Theodorus shot himself with an inscribed pistol that Queen Victoria had earlier presented to him; and General Napier and his victorious but not imperialistic army marched away for good (and for the betterment of the British Museum’s collections through the acquisition of invaluable Ethiopian works of art and literature as loot). The Emperor’s 7-year-old son Alamayu was brought to England and educated as a ward of Queen Victoria at Rugby and Sandhurst, to die young, homesick no doubt for Abyssinia, and be buried in the Chapel Royal at Windsor Castle.

Drawing largely on hitherto untapped sources (besides family papers made available some years ago by Napier’s son, the Hon. Albert Napier, then still alive), in the Public Record Office, the India Office library, and the Royal Archives at Windsor Castle, Darrell Bates has produced an exact and unvarnished but continually entertaining and exciting account of a confrontation that was in some respects tragic, in others heroic, frequently hilarious, and wonderfully full of high Victorian panache and style.

Sir Darrell Bates, C.M.G., C.V.O., spent some time in Ethiopia during his wartime service in the King’s African Rifles (1940-43), having worked in the Colonial administration in Tanganyika. After periods in the Seychelles and Somaliland, he was posted to Gibraltar (where Lord Napier had been made Governor after the Magdala campaign) as Colonial Secretary in 1953, and retired in 1968 to live and write in Cornwall. He has written several books of short stories, reminiscences, and biography, interspersed with articles for The Economist and The Times, and writing and broadcasting for the B.B.C.

Source: rabats avant et arrière de la jaquette.

Vu par Richard Pankhurt

The rise of Emperor Téwodros of Ethiopia, the would-be moderniser, and unifier; his use of foreign missionaries to cast him cannon; his despatch of a letter to Queen Victoria which the Foreign Office left unanswered; his consequent quarrel with the British Government from whom he had hoped to obtain assistance; his imprisonment of a British consul, an envoy from Queen Victoria and a handful of other Europeans; the despatch against his mountain fortress of Magdala of a powerfully armed Anglo-Indian expedition complete with breech-loading Snider rifles, elephants and a twelve-mile long railway; his dramatic decision to commit suicide rather than fall into the hands of the victorious British; the looting by British troops of a thousand manuscripts he had collected; and the withdrawal of the British without any attempt at establishing a colony or protectorate—these are events which will for ever fascinate students of Ethiopian, African and indeed world history. The Magdala story is destined to be retold by writers of many nationalities and from various angles—and will soon be the subject of a film spectacular.

Sir Darrell Bates, C.M.G., C.V.O., a former British Colonial Secretary in Gibraltar, became interested in these matters for a fortuitous reason—because Robert Napier, the commander of the British expedition to Magdala, ended his career as Governor of that island. Sir Darrell’s initial preoccupation with Napier, however, gradually widened, and at least partially justifies his sub-title.

The Abyssinian Difficulty, though telling us little about Téwodros and his aspirations, presents a gripping account of the Emperor’s conflict with the British Government, as well as of the Magdala expedition, and the Ethiopian response thereto. Sir Darrell writes from a somewhat ethnocentric point of view. He is, however, sufficiently detached to describe the inefficiencies on the British side—28,673 of the expedition’s 36,000 mules were for example ‘destroyed or abandoned’, and to raise the question why Napier decided to attack Magdala after Tewodros had released the prisoners whose liberation was the declared raison d’être of the campaign.

Sir Darrell, though remiss in not clearly citing his authorities, provides a valuable bibliography, and has made good use of some little-known sources. He appears, surprisingly enough, to be the first author extensively to utilise Dr Austin’s despatches to The Times (which clearly would repay the attention of an enterprising reprint firm).

Source : Reviews of Books – Comptes Rendus, Africa , Volume 50 , Issue 3 , July 1980 , pp. 321.